Abstract: Grab a hot chocolate and get cosy for a fireside chat about a candle's flame and the embers left behind. Following the lead of Michael Faraday in his 1848 Royal Institution Christmas lectures, I will provide an updated chemical history of a candle - including some experiments for you to try at home. The fun doesn't end there - after a flame is extinguished, there's a wealth of discoveries to be made in the embers. Understanding the structure of these carbon materials begins with Rosalind Franklin, best-known for her work on DNA, and continues with simulations on a supercomputer. While there are still many unanswered questions around flames and carbon materials, these recent insights are enlightening and important for cleaning up our planet.

Showing posts with label flexoelectricity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label flexoelectricity. Show all posts

Wednesday, 10 June 2020

The Chemical History of a Candle and Structure of an Ember - Webinar

Tuesday, 19 June 2018

Can curved molecules in flames help reduce soot pollution?

Soot is a serious problem which impacts human and the planet's health. The world health organisation estimates that in 2012 seven million people died or 1/8 total deaths around the world, from air pollution with around half from ambient air pollution and the rest from indoor air pollution from cooking on inefficient stoves (WHO). Soot emissions are also the biggest contributor to global warming after the greenhouse gases. So how do we stop soot from forming? The first step is to understand the mechanism by which soot forms, which is surprisingly still not yet fully understood. We have just published an article considering the impact of curved aromatic molecules on the formation mechanism of soot (here is a link to the preprint).

|

| Credit |

So what is currently understood about soot formation? The animation below will aid in illustrating soot formation. It shows the inside of a small lawn mower motor with a transparent plastic engine head allowing for a high-speed camera to capture the combustion inside the engine.

|

| Credit |

A small spark ignites the petrol and air mixture and a blue flame is seen to spread through the cylinder. At the flame front there is enough oxygen and so the fuel burns completely to carbon dioxide and water with the blue colour (the colour is due to excited intermediates C2*, CH* and OH*). However, not all of the flame has enough oxygen to completely combust. Behind the flame front, a build-up of carbon molecules forms soot which glows yellow because it is heated by the combustion. So the yellow colour you see in the figure is soot which is being exhausted into the atmosphere. You can confirm that the yellow colour is from soot at home by placing a metal spoon into the yellow part of the flame and picking up black soot on the spoon.

From the animation inside the engine, you will also have seen the complexity of the flame. To simply the system we often use simple burners to study soot formation which produce very stable candle-like flames (diffusion flame). Below is one of the burners with a schematic to highlight the molecules involved in soot formation. The steps for soot formation are as follows:

- Precursor pyrolysis - the fuel breaks down and without enough oxygen a build up of carbon molecules - primarily acetylene occurs.

- PAH formation - The acetylene C2H2 reacts through a radical chain reaction into aromatic fused ring molecules.

- Inception/nucleation - Small carbon nanoparticle nuclei are formed

- Growth - Some of these nuclei grow to become primary particles tens of nanometres in size.

- Aggregation/agglomeration - Primary particles stick together and form fractal-like stringy aggregates.

Step three (inception) is currently the most difficult to understand. Formation of small carbon nanoparticles from aromatic molecules in the flame happens too quickly to be a chemical reaction and must include some physical sticking or clustering to explain the speed of formation. My research group has previously determined that flat PAH (planar aromatics with only hexagonal rings) have been found to not be sticky enough to overcome the high temperatures where soot forms in a flame (~1000-1250°C). This thermal energy shakes the clusters apart.

So what about these curved PAH molecules? It is well known that they are present in soot, corannulene (a simple curved PAH with a pentagon ring surrounded by hexagonal rings) has been extracted from soot and if you decrease the pressure around the flame completely enclosed spherical cages of carbon (fullerenes) can be produced.

curved PAH corannulene (left and below click and drag to move the grey model around and zoom with your mouse wheel) and closed cage fullerene (right)

We have previously shown that these molecules contain a large electric polarisation which might be important. So how do these polarised cPAH effect soot formation? In this paper we considered three questions:

- What causes lead to curvature and how small do the molecules need to become curved?

- Can curved PAH cluster together in the flame where soot forms (~1000-1250°C)?

- What other interactions could cPAH have with other precursors (e.g. chemi-ions)?

What causes the curvature and how small do the molecules need to be to curve? Using computational chemistry we could calculate the geometry of lots of different curved aromatic molecules. We found the minimum size is 6 rings to curve a PAH with at least one ring being pentagonal.

It turns out the pentagon containing PAH are planar for larger molecules than you would expect from considering a perfect net of pentagons and hexagons. We found this is due to the bonding of electrons on the top and bottom of the molecule favouring planar geometries which are only overcome when the in-plane bonds are strong enough to pull the molecule into a curved configuration.

Can curved PAH cluster together in the flame where soot forms (~1000-1250°C)? Using another calculation method we worked out how sticky the cPAH are compared with their planar cousins (more negative binding energies means more strongly bound) shown below. Triangles indicate flat PAH and squares indicate cPAH. We found that for one or two pentagons, cPAH have similar binding energies to flat PAH. With three or greater number of pentagons the cPAH bound with less energy than the same sized flat PAH.

We have previously shown that for the size of flat PAH in soot it is unlikely to be able to stablise the small clusters in the soot inception zone. So for cPAH with up to two pentagons, we expect the situation to be similar and with three or more the nucleation is definitely not possible.

What other interactions could cPAH have with other precursors? In the schematic near the top of the article, we also highlighted some ionic species called chemi-ions (coloured blue). There is a surprising amount of these charges in flames which form from reactions between an excited C-H molecule (which is one of the intermediates that glows blue). When excited CH reacts with oxygen or acetylene it ejects an electron and becomes positively charged. The impact of these charges can be quite dramatic if you apply an electric field. At a given voltage you can also see the flame conduct electricity with arcs going through the flame.

Soot formation can also be halted with a strong electric field. The picture below shows with a counterflow burner with fuel from below and air from above. With no electric field applied a yellow sooting flame is found. Applying a strong electric field removes the soot from the flame leaving a blue clean burning flame. This has been explained as charged nuclei and carbon being rapidly sucked out of the flame by the strong electric field.

|

| Top - counterflow diffusion flame without an electric field applied. Bottom - with a strong electric field applied Credit: Lawton and Weinberg 1969 |

Curved aromatics are significantly polar and might explain these electrical aspects of soot formation. The interaction between charge and a dipolar molecule is long range and substantial. The plot below shows a range of curved PAH (covering the range of sizes we see in the flame 10-20 rings) with their binding energy to a charge. To give you a sense of what sort of energies are needed to hold something together at flame temperatures around 165 kJ/mol is usually quoted.

There is quite a lot more work needed to consider this ionic interaction and what impact soot formation here are some of the questions that need answering:

- How many cPAH are present in early soot nanoparticles?

- What is the polarity of the cPAH in early soot?

- Can a cluster of cPAH be stabilised at high temperatures in a flame with a chemi-ion?

- Is flexoelectricity involved in any other way in soot formation?

So the question Can curved molecules help reduce soot pollution? is yet to be fully answered. We will be presenting these results at the next combustion symposium in Dublin at the end of next month and have more results on the way.

Thursday, 9 November 2017

Polar aromatic molecules

We have recently published a paper on an interesting class of curved aromatic molecules. Here is an interactive 3D model of one of the molecules we studied. Click and drag to rotate the model in 3D, zoom in and out with the mousewheel.

In short

- We found that this curving of the molecules shifted the electrons from the concave to the convex side of the molecule which makes quite a large electric field.

- This is quite a strange finding mainly because most aromatic molecules are usually considered electrically non-polar.

- These curved molecules have been spotted (using electron microscopes) in soot particles, carbon battery electrodes and carbon water filters.

- The electric field around these molecules will have a huge impact on how they interact with polar molecules such as water and many pollutants the electric field will also provide significant interactions with ions such as lithium used in batteries.

Want to know more about polar molecules, why these aromatic molecules are polar and more about what this could mean for carbon research please read on.

What are polar molecules?

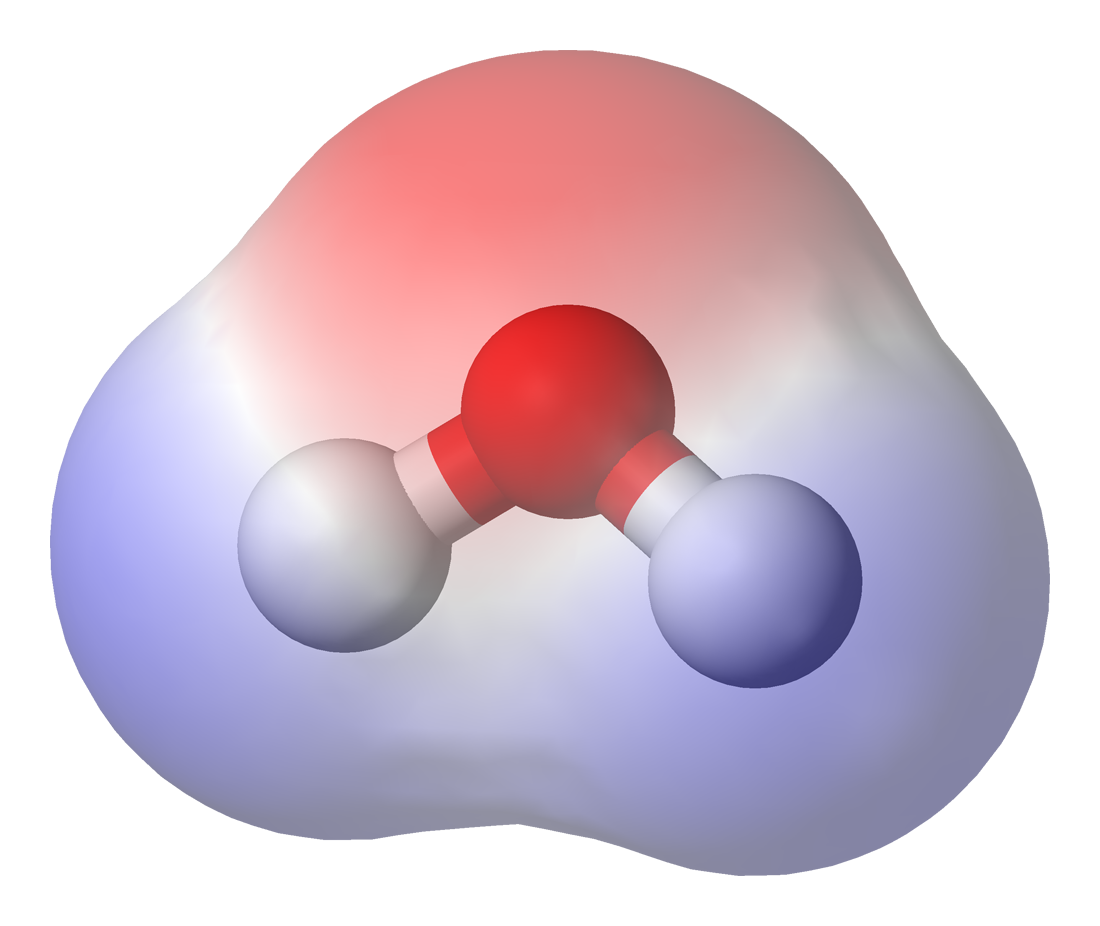

You may have heard that water is polar and other substances are non-polar like oil. Polar refers to the electric field around the molecule which has two poles a negative and a positive pole/end. For two opposite charges the potential is plotted below where red denotes a negative potential and blue a positive potential. The lines are lines of constant potential and are like contour lines on a map of a volcano denoting regions with the same value/height.

|

| Credit: link |

The dipole moment is defined as the distance the charges are separated multiplied by the difference between the two charges. Two opposite elementary charges (charge of an electron) separated by 0.1 nm gives a dipole moment of 4.8 D (debyes).

The atomic nuclei are small and positively charged and can be considered as point charges however the electrons are not well defined but spread out over space due to quantum mechanics. In this case we can define the molecular dipole as a sum of the dipole moment from the nuclei, as point charges, and the dipole from the electron density which can be unevenly shared between the atoms. The picture below on the left shows the electron density in gray at a certain value (kind of like a 3D contour) as a surface for hydrochloric acid. You can see more electron density on the chlorine atom, this is mainly because the chlorine nucleus has a charge of +17 compared with the hydroge nuclei which only has a charge +1, but there is also even more electron density on the chlorine nuclei than enough to cancel the positive nuclei making the potential on this surface more negtaive on the chlorine side than the hdyrogen side (seen in the figure below right). Giving HCl a dipole moment of 1.08 D.

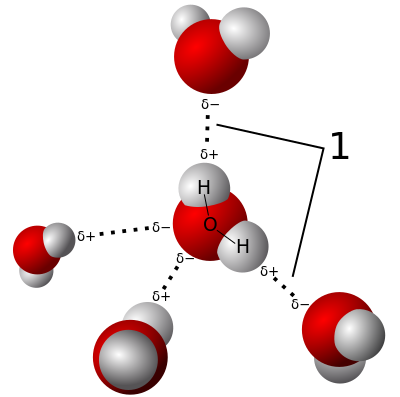

The cloud of electrons becomes very repulsive when molecules approach each other past the surface we have drawn. So you can think of this surface as the place where the molecules will touch each other (this surface is near the electron density value of 0.001 eÅ$^{-3}$). You might know that opposite charges attract so if you line up two molecules of HCl with the negative chlorine of one pointing towards the positive hydrogen of the other they will be attract each other. Below is a picture showing the attractive and repulsive ways of orienting two polar molecules. The Greek delta character δ is used to denote partially charged regions as the ends of the molecule do not have point charge of +1 but are only partially charged.

| Credit: link and recoloured |

Water is the most commonly known polar molecule. Below I am plotting the electric field around a water molecule along with the potential at the interaction surface.

As these is a assymmetry to the electric potential (i.e. one side is positive and the other negative) water has a dipole moment of 1.85 D in the gas phase. This allows water to strongly interact with other water molecules and is what holds water together as a liquid at room temperature when similar sized molecules such as methane are no where near being liquid. Methane is a gas at room temperature and needs to be cooled to -161.5 °C before it becomes a liquid. Below is an animation of water molecules attracting each other (often called a hydrogen bond). Apart from the amazing fact of being a liquid at room temperature water forms a strange cage structure when it freezes which takes up more room than the liquid meaning it is less dense and allows solid water to uniquely float on the liquid.

|

| Credit: CSIC |

|

| Credit: Qwerter |

If you have a balloon handy you can do a simple experiment to convince yourself that water is polar. Rubbing a balloon with a cloth or on your head removes positive charge and leaves the balloon with a negative charge. Holding the balloon near a stream of water the positive side of the water molecule will be attracted to the negative charge on the balloon and it will bend the water toward itself.

|

Credit: Link

|

To put a scale in your mind as to the common range of dipole moments I have added the table below.

| Table of the dipole moment in Debye units (1 D = 3.336×10^-30 C m) taken from Israelachvili 1992 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Molecule | Formula | Dipole moment |

| Ethane | $\text{C}_2\text{H}_6$ | 0 |

| Benzene | $\text{C}_6\text{H}_6$ | 0 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | $\text{CCl}_4$ | 0 |

| Carbon dioxide | $\text{CO}_2$ | 0 |

| Chloroform | $\text{CCl}_3$ | 1.06 |

| Hydrochloric acid | $\text{HCl}$ | 1.08 |

| Ammonia | $\text{NH}_3$ | 1.47 |

| Phenol | $\text{C}_6\text{H}_5\text{OH}$ | 1.5 |

| Ethanol | $\text{C}_2\text{H}_5\text{OH}$ | 1.7 |

| Water | $\text{H}_2\text{O}$ | 1.85 |

| Cesium Chloride | $\text{CsCl}$ | 10.4 |

You will notice the aromatic molecule benzene does not have a dipole moment in the next section we will explore why this is the case.

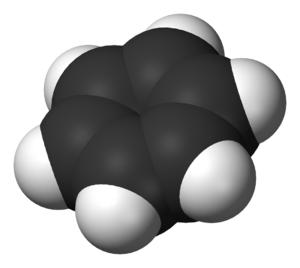

Are planar aromatic molecules polar?

Benzene is the simplest aromatic molecule. It is made of six carbon atoms arranged into a hexagonal ring (below left). Adding six more hexagonal rings of carbon you can produce coronene a large polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon with seven hexagonal rings of carbon (below right).

Plotting below the electrostatic potential of these two molecules looking side on (perpendicular to the aromatic plane) the electric field around planar aromatic molecules can be viewed. Around the hydrogen atoms, often called the rim of the PAH, the potential is positive. The top and bottom near the carbon atoms is negative. This can be explained by the bonding but we will leave this for another post.

Plotting below the electrostatic potential of these two molecules looking side on (perpendicular to the aromatic plane) the electric field around planar aromatic molecules can be viewed. Around the hydrogen atoms, often called the rim of the PAH, the potential is positive. The top and bottom near the carbon atoms is negative. This can be explained by the bonding but we will leave this for another post.

As you can see there is no one side that is negative and another that is positive (no assymmetry). The potentials are mirror images. There is no net dipole moment for planar aromatic molecules i.e. they are non-polar. This means they will only have weak interactions with polar molecules such as water making aromatics insoluble in water.

This arrangement of charged regions is called a quadrupole and is one moment higher than the dipole. Below are some point charge representations of a quadrupole and a contour plot of a quadrupole.

So how can we make an aromatic molecule polar. The next section will show that curvature integration is the key.

Curved aromatics are polar

Curvature is integrated into aromatic molecules when a non-hexagonal ring of carbon atoms is integrated into the normally closed

Corannulene is experimentally known to contain a dipole moment of 2.07 D. This is quite a large dipole moment close to that of water. Below I have plotted the electric field around water, corannulene and coronene far away from the molecules (around 4 nm).

Comparing corannulene to water a similar potential is seen at the far field, however, close to the molecule there is a negative potential near the concave side of the bowl. Comparing corannulene to coronene the positive region around the hydrogen atoms is similar in both molecules, however, there is a shift of the negative potential to the convex surface of the curved corannulene. This turns out to be due to an effect called flexoelectricity. By flexing the molecule you shift electrons from the concave to the convex surface leading to the dipole you see.

We used a supercomputer to calculate the electron density around some very large curved aromatic molecules. From this we could determine the dipole moment with very good accuracy (less than 2% error for corannulene compared with experiment). The figure below shows the strong scaling of the dipole moment with the size of the molecules. The size range found in soot and other carbon materials is around 10-20 aromatic rings shown as the shaded grey area. This indicates that curved fragments in carbon materials can have a significant dipole moment of 2-6 D.

Why is this result so exciting?

There are many carbon materials that contain these curved aromatic molecules such as soot (pollutant from engines that contributes to global warming), carbon blacks (used in inks and tires), activated carbon (used in water filters, they are also used as an antidote to poisons as they are very good at sucking up organic molecules and metals) and battery carbon electrodes. To date very few people have considered these molecules to contain a dipole moment and what impact that has on their performance.

The considerable dipole moment we predict will have a huge impact on how the carbon materials interact with other molecules here are a few potential important interactions.

- In batteries positively charged lithium ions will interact strongly with the dipole moment on the curved molecules.

- In soot formation charged chemi-ions will interact strongly with curved aromatic molecules in the flame.

- In activated carbon a strong interaction is expected between the dipole moment and adsorbents that are charged or polar.

If you are interested in how you can include these effects into computer simulations of carbon systems read on.

Simulating carbon materials with curvature in the computer

Many important properties of carbon materials could be potentially optimised if we can tune the curvature in carbon materials. A simple mathematical representation in the computer is needed to model these properties. A common representation of the electric field in computer simulations around the molecule is to use point charges at each atom (usually much less than an atomic charge) and then fit the electrostatic potential around the molecule by adjusting these charges to match the electric field far away from the molecule. We usually also add a repulsive mathematical function so that the molecule cannot get too close to another. This means the potential is only important outside this region which can be thought of as an interaction surface. This means we need to correctly describe the electrostatic at and outside the interaction surface. A previous PhD student Tim Totton along with Dr. Alston Misquitta developed a forcefield for planar PAH molecules and found that atomic centred point charges do a good job of describing the electric field around these molecules. Below is a picture of the electric potential around coronene calculated from a full quantum mechanical simulation (DFT) and using point charges centred at each atom. The far right shows an overlay of the two showing remarkable agreement.

When we tried the same fitting of the electrostatic potential for corannulene using atom centred point charges we found a very bad fit. The first problem was the magnitude of the dipole moment was reduced to 1.73 D. The reason the fit was so poor is due to the flexoelectric effect which occurs perpendicular to the rings. This means dipoles must be included on the pentagonal carbon atoms to correctly describe these. We made use of atom-centred multipoles (monopole+dipole+quadrupole) to correctly describe the polarisation and the quadrupoles provide better description of the potential around the hydrogen atoms. Below is a figure of the potential around corannulene for point charges and for multipoles.

These atom centred multipoles descriptions of molecular electrostatics have recently been integrated into different molecular dynamics packages such as Tinker, OpenMM and DL_POLY. Get in contact if you are interested in simulating a certain carbon system and I would be happy to work with you on it.

Wednesday, 1 November 2017

Curving aromatic molecules

|

| Credit: link |

Aromatic molecules such as benzene and coronene (shown above) contain a hexagonal arrangement of carbon atoms. This gives a flat planar structure due to the geometry of hexagonal rings which are able to tessellate in two dimensions (see the tessellating tiles in the picture below). You can think of these hexagonal aromatics being like a flat saucers.

|

| Credit: Paula Soler-Moya |

A hexagonal arrangement of carbon atoms is the most stable (making grapite the most stable form of carbon, being made up of hexagonal sheets of carbon). The molecule shown below left (benzo(ghi)fluoranthene) would at lower temperatures and over longer times rearrange and form a completely hexagonal structure but in the formation of soot in a flame a faster reaction has been found with acetylene which forms the less stable corannulene molecule with a pentagon trapped within. Integration of this non-hexagonal rings into a hexagonal lattice does not leads to a net that can be nicely tessellated on a 2D surface but leads to a 3D warped structure - a bowl-like geometry. I have embeded an interactive 3D models of these two molecules so you can see this 3D curvature for yourself (click and drag to move the grey models around and zoom with your mouse wheel).

|

| Credit: Ikea |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)