In short

- We found that this curving of the molecules shifted the electrons from the concave to the convex side of the molecule which makes quite a large electric field.

- This is quite a strange finding mainly because most aromatic molecules are usually considered electrically non-polar.

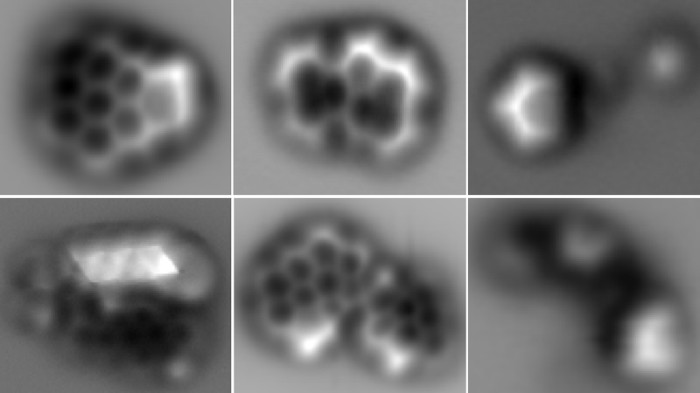

- These curved molecules have been spotted (using electron microscopes) in soot particles, carbon battery electrodes and carbon water filters.

- The electric field around these molecules will have a huge impact on how they interact with polar molecules such as water and many pollutants the electric field will also provide significant interactions with ions such as lithium used in batteries.

You can read the full preprint of the paper for free on our website

Want to know more about polar molecules, why these aromatic molecules are polar and more about what this could mean for carbon research please read on.

What are polar molecules?

You may have heard that water is polar and other substances are non-polar like oil. Polar refers to the electric field around the molecule which has two poles a negative and a positive pole/end. For two opposite charges the potential is plotted below where red denotes a negative potential and blue a positive potential. The lines are lines of constant potential and are like contour lines on a map of a volcano denoting regions with the same value/height.

The dipole moment is defined as the distance the charges are separated multiplied by the difference between the two charges. Two opposite elementary charges (charge of an electron) separated by 0.1 nm gives a dipole moment of 4.8 D (debyes).

The atomic nuclei are small and positively charged and can be considered as point charges however the electrons are not well defined but spread out over space due to quantum mechanics. In this case we can define the molecular dipole as a sum of the dipole moment from the nuclei, as point charges, and the dipole from the electron density which can be unevenly shared between the atoms. The picture below on the left shows the electron density in gray at a certain value (kind of like a 3D contour) as a surface for hydrochloric acid. You can see more electron density on the chlorine atom, this is mainly because the chlorine nucleus has a charge of +17 compared with the hydroge nuclei which only has a charge +1, but there is also even more electron density on the chlorine nuclei than enough to cancel the positive nuclei making the potential on this surface more negtaive on the chlorine side than the hdyrogen side (seen in the figure below right). Giving HCl a dipole moment of 1.08 D.

The cloud of electrons becomes very repulsive when molecules approach each other past the surface we have drawn. So you can think of this surface as the place where the molecules will touch each other (this surface is near the electron density value of 0.001 eÅ$^{-3}$). You might know that opposite charges attract so if you line up two molecules of HCl with the negative chlorine of one pointing towards the positive hydrogen of the other they will be attract each other. Below is a picture showing the attractive and repulsive ways of orienting two polar molecules. The Greek delta character δ is used to denote partially charged regions as the ends of the molecule do not have point charge of +1 but are only partially charged.

|

|

| Credit: link and recoloured |

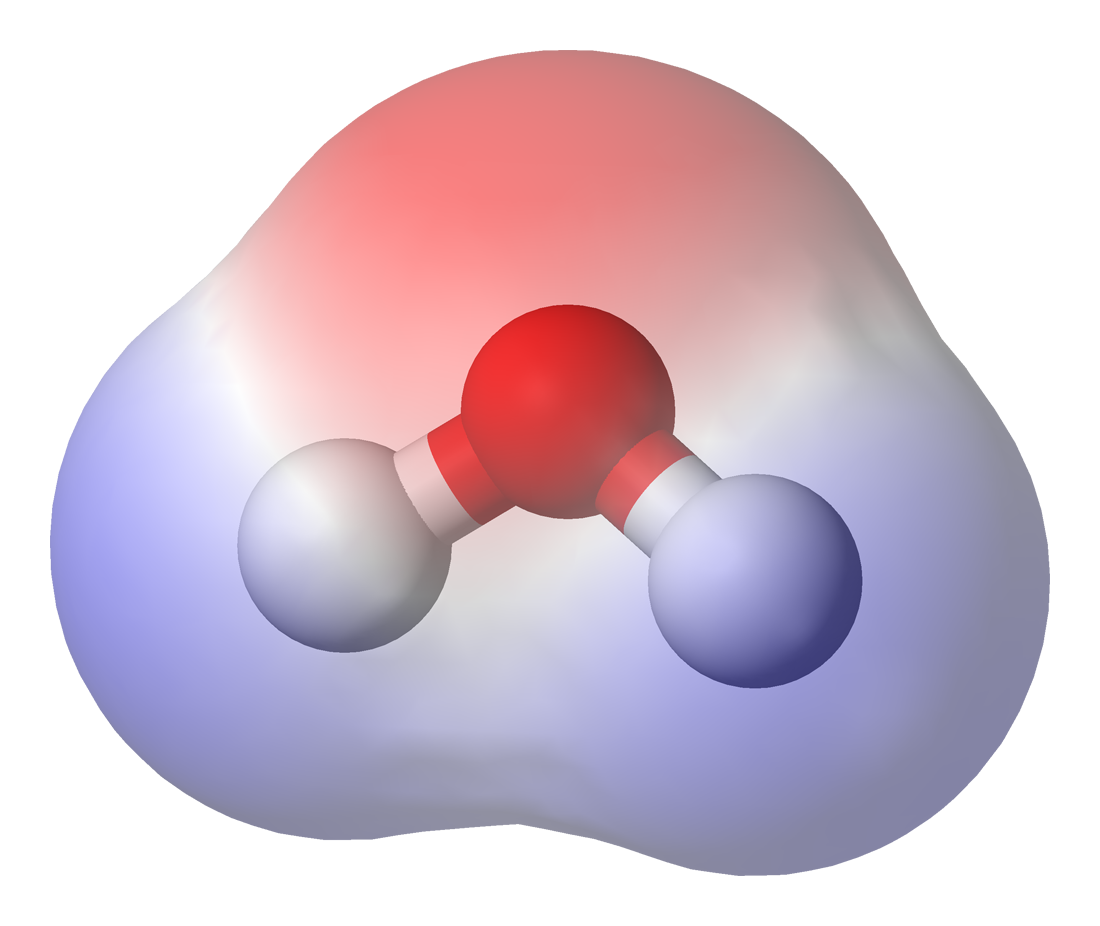

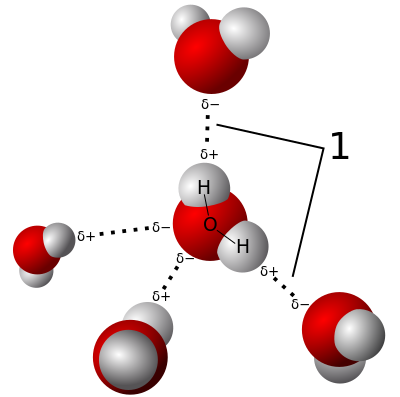

Water is the most commonly known polar molecule. Below I am plotting the electric field around a water molecule along with the potential at the interaction surface.

As these is a assymmetry to the electric potential (i.e. one side is positive and the other negative) water has a dipole moment of 1.85 D in the gas phase. This allows water to strongly interact with other water molecules and is what holds water together as a liquid at room temperature when similar sized molecules such as methane are no where near being liquid. Methane is a gas at room temperature and needs to be cooled to -161.5 °C before it becomes a liquid. Below is an animation of water molecules attracting each other (often called a hydrogen bond). Apart from the amazing fact of being a liquid at room temperature water forms a strange cage structure when it freezes which takes up more room than the liquid meaning it is less dense and allows solid water to uniquely float on the liquid.

If you have a balloon handy you can do a simple experiment to convince yourself that water is polar. Rubbing a balloon with a cloth or on your head removes positive charge and leaves the balloon with a negative charge. Holding the balloon near a stream of water the positive side of the water molecule will be attracted to the negative charge on the balloon and it will bend the water toward itself.

|

|

|

To put a scale in your mind as to the common range of dipole moments I have added the table below.

| Table of the dipole moment in Debye units (1 D = 3.336×10^-30 C m) taken from Israelachvili 1992 |

| Molecule |

Formula |

Dipole moment |

| Ethane |

$\text{C}_2\text{H}_6$ |

0 |

| Benzene |

$\text{C}_6\text{H}_6$ |

0 |

| Carbon tetrachloride |

$\text{CCl}_4$ |

0 |

| Carbon dioxide |

$\text{CO}_2$ |

0 |

| Chloroform |

$\text{CCl}_3$ |

1.06 |

| Hydrochloric acid |

$\text{HCl}$ |

1.08 |

| Ammonia |

$\text{NH}_3$ |

1.47 |

| Phenol |

$\text{C}_6\text{H}_5\text{OH}$ |

1.5 |

| Ethanol |

$\text{C}_2\text{H}_5\text{OH}$ |

1.7 |

| Water |

$\text{H}_2\text{O}$ |

1.85 |

| Cesium Chloride |

$\text{CsCl}$ |

10.4 |

You will notice the aromatic molecule benzene does not have a dipole moment in the next section we will explore why this is the case.

Are planar aromatic molecules polar?

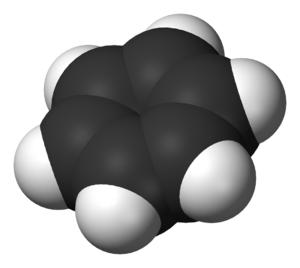

Benzene is the simplest aromatic molecule. It is made of six carbon atoms arranged into a hexagonal ring (below left). Adding six more hexagonal rings of carbon you can produce coronene a large polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon with seven hexagonal rings of carbon (below right).

Plotting below the electrostatic potential of these two molecules looking side on (perpendicular to the aromatic plane) the electric field around planar aromatic molecules can be viewed. Around the hydrogen atoms, often called the rim of the PAH, the potential is positive. The top and bottom near the carbon atoms is negative. This can be explained by the bonding but we will leave this for another post.

As you can see there is no one side that is negative and another that is positive (no assymmetry). The potentials are mirror images. There is no net dipole moment for planar aromatic molecules i.e. they are non-polar. This means they will only have weak interactions with polar molecules such as water making aromatics insoluble in water.

This arrangement of charged regions is called a quadrupole and is one moment higher than the dipole. Below are some point charge representations of a quadrupole and a contour plot of a quadrupole.

So how can we make an aromatic molecule polar. The next section will show that curvature integration is the key.

Curved aromatics are polar

Curvature is integrated into aromatic molecules when a non-hexagonal ring of carbon atoms is integrated into the normally closed

Corannulene is experimentally known to contain a dipole moment of 2.07 D. This is quite a large dipole moment close to that of water. Below I have plotted the electric field around water, corannulene and coronene far away from the molecules (around 4 nm).

Comparing corannulene to water a similar potential is seen at the far field, however, close to the molecule there is a negative potential near the concave side of the bowl. Comparing corannulene to coronene the positive region around the hydrogen atoms is similar in both molecules, however, there is a shift of the negative potential to the convex surface of the curved corannulene. This turns out to be due to an effect called flexoelectricity. By flexing the molecule you shift electrons from the concave to the convex surface leading to the dipole you see.

We used a supercomputer to calculate the electron density around some very large curved aromatic molecules. From this we could determine the dipole moment with very good accuracy (less than 2% error for corannulene compared with experiment). The figure below shows the strong scaling of the dipole moment with the size of the molecules. The size range found in soot and other carbon materials is around 10-20 aromatic rings shown as the shaded grey area. This indicates that curved fragments in carbon materials can have a significant dipole moment of 2-6 D.

Why is this result so exciting?

There are many carbon materials that contain these curved aromatic molecules such as soot (pollutant from engines that contributes to global warming), carbon blacks (used in inks and tires), activated carbon (used in water filters, they are also used as an antidote to poisons as they are very good at sucking up organic molecules and metals) and battery carbon electrodes. To date very few people have considered these molecules to contain a dipole moment and what impact that has on their performance.

The considerable dipole moment we predict will have a huge impact on how the carbon materials interact with other molecules here are a few potential important interactions.

- In batteries positively charged lithium ions will interact strongly with the dipole moment on the curved molecules.

- In soot formation charged chemi-ions will interact strongly with curved aromatic molecules in the flame.

- In activated carbon a strong interaction is expected between the dipole moment and adsorbents that are charged or polar.

If you are interested in how you can include these effects into computer simulations of carbon systems read on.

Simulating carbon materials with curvature in the computer

Many important properties of carbon materials could be potentially optimised if we can tune the curvature in carbon materials. A simple mathematical representation in the computer is needed to model these properties. A common representation of the electric field in computer simulations around the molecule is to use point charges at each atom (usually much less than an atomic charge) and then fit the electrostatic potential around the molecule by adjusting these charges to match the electric field far away from the molecule. We usually also add a repulsive mathematical function so that the molecule cannot get too close to another. This means the potential is only important outside this region which can be thought of as an interaction surface. This means we need to correctly describe the electrostatic at and outside the interaction surface. A previous PhD student Tim Totton along with Dr. Alston Misquitta developed a forcefield for planar PAH molecules and found that atomic centred point charges do a good job of describing the electric field around these molecules. Below is a picture of the electric potential around coronene calculated from a full quantum mechanical simulation (DFT) and using point charges centred at each atom. The far right shows an overlay of the two showing remarkable agreement.

When we tried the same fitting of the electrostatic potential for corannulene using atom centred point charges we found a very bad fit. The first problem was the magnitude of the dipole moment was reduced to 1.73 D. The reason the fit was so poor is due to the flexoelectric effect which occurs perpendicular to the rings. This means dipoles must be included on the pentagonal carbon atoms to correctly describe these. We made use of atom-centred multipoles (monopole+dipole+quadrupole) to correctly describe the polarisation and the quadrupoles provide better description of the potential around the hydrogen atoms. Below is a figure of the potential around corannulene for point charges and for multipoles.

These atom centred multipoles descriptions of molecular electrostatics have recently been integrated into different molecular dynamics packages such as Tinker, OpenMM and DL_POLY. Get in contact if you are interested in simulating a certain carbon system and I would be happy to work with you on it.