tl;dr Our new preprint "Carbonaceous nanoparticle formation in flames" is out.

The paper is now published in Progress in Energy and Combustion Science

A middle way can refer to many things. In common usage it

refers to a comprise between two positions. In philosophy or religion, it can

refer to a rejection of extremes as exemplified by Aristotle’s golden mean that

“every virue is a mean between two extremes, each of which is a vice”. In logic

it can refer to a fallacy - halfway between a lie and a truth is still a lie

and therefore some care is required in proposing such compromising positions.

In science it has been used for a variety of justifiable and unjustifiable

positions. One famous example being the middle way between physical scales and

another being a position we recently put forward for the formation of the

pollutant soot.

In the influential paper “The middle way” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA in 2000, Laughlin et al. discussed the challenge in probing the scale between the atomic and macroscopic dimensions. In this mesoscopic region significant gaps exists in our understanding of how atoms and molecules interact, organise and form complex structures. This intermediate scale is too large to be measured by analytical chemical approaches and too small to be approached from the macroscale. Examples include protein folding, high temperature superconductors and disordered or topologically frustrated materials.

Our recent study on the formation of the pollutant soot illustrates the challenges probing the mesoscopic scale nicely. Figure 1 below shows a schematic of the transformation of fuel molecules into the pollutant soot. Only in the last 5 years have experimental techniques allowed for the aromatic soot precursor molecules as well as the earliest nanoparticles to both be directly imaged. Mass spectrometry has also allowed for the mass of the clustering molecules to be measured during soot formation. However, the mechanism by which these molecules cluster continues to baffle combustion scientists. The prize sought is the ability to understanding and potentially halt the emission of these toxic pollutants from internal combustion engines that damage almost every organ in our bodies as well as contribute to climate change.

|

Figure 1 – Schematic for the transformation of fuel into

soot inside a flame with insets showing the experimental results from which the

schematic is derived. High resolution atomic force microscopy (HRAFM)from

Commodo et al. 2019, Helium ion microscopy (HIM) from Schnek et al. 2013, high

resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) from Martin et al. 2018 and

scanning electron microscopy (SEM) from Orion carbons.

Our modelling efforts also struggle to traverse the molecule

to nanoparticle transition in soot formation. There are two main classes of

models that have been proposed for soot formation. The first is physical

nucleation where aromatic molecules grow until the intermolecular interactions

between the molecules allows them to stick together and condense. The second is

chemical inception where bonds form between the molecular systems. Only

recently have accurate computational approaches been developed to explore these

suggestions.

Concerning physical nucleation, Prof. Kraft’s group worked

with the physical chemist Prof. Alston Misquitta (Queen Mary University) in the

2010s to accurately compute the intermolecular interactions between aromatic

species (using a symmetry adapted perturbation with a hybrid density functional

approach). From these results it was clear that the clustering species seen in

the flame are far too small to possess the significant intermolecular energies

required for physical nucleation mechanism. For my PhD, I explored electrical

enhancements to physical nucleation that arise from curved aromatic species

that possess a strong electric polarisation. While this electrical effect may

help explain the electrical control of soot formation it alone cannot justify a

nucleation mechanism either.

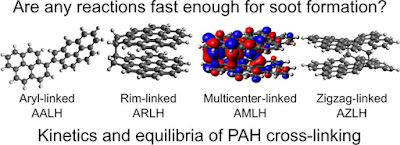

Concerning chemical inception, we recently undertook a

systematic study of the bonds that could form between reactive aromatic soot

precursors with Prof. Xiaoqing You’s group at Tsinghua University (made

possible by the CARES programme). This was only possible due to the direct

imaging of the reactive aromatics in 2019 (see Figure 1) and the recent

advances in density functional computational techniques optimised for radicals

(the meta hybrid GGA density functional method M06-2X). Figure 2 shows the

systematic comparison that was possible with such an approach for small

aromatic molecules. The green coloured grid squares correspond with thermally

stable species. Mr Angiras Menon was recently able to compute the rate at which

each of these crosslinks forms and compared them with the speed of soot

formation. We found that for these small species none of the crosslinks formed

sufficiently fast enough to explain the rapid clustering of molecules into soot

nanoparticles.

|

| Figure 2 – Bond energy between various reactive aromatic soot precursors. Green indicates bonds that have enough thermal stability to be considered as important in flames. |

These detailed studies left us with the uncomfortable conclusion that the two main routes proposed for soot formation were unable to describe it. However, something did catch our attention crosslinks that allowed the molecules to both bond and stack, see Figure 2 B), C) and D) sites. This opened up another possibility that both physical and chemical mechanisms could cooperatively contribute to soot formation. Upon exploring these possibilities, we found that π-radicals on five membered rings, site B), formed highly localised states that did not become deactivated as the molecule grew in size, unlike their hexagonal ring equivalent, thereby remaining highly reactive. This allowed for an additive contribution between the physical interactions and the chemical bond only in these so-called aromatic rim-linked hydrocarbons (ARLH). Figure 3 shows the various mechanisms placed on a C/H versus molecular weight schematic to show the middle way suggested.

|

Figure 3 – A middle way is schematically shown between physical and chemical mechanisms for soot formation. |

As mentioned at the beginning of this article claims to

middle ways are poor arguments unless they can be justified. Currently, we have

shown that the addition of physical interactions and chemical bonding considerably

increases the thermodynamic stability of aromatic rim-linked hydrocarbons.

However, we have yet to show that such species can explain the rapid formation

of soot in the flame. This requires the collision efficiency between these

species and the concentration of the localised π-radicals on five-membered rings to

be determined. Experiments are underway in the community to probe such species

and close this missing gap between the micro and mesoscale of soot formation.